Quick Examples for Jac Features

For each key feature in Jac/Jaseci, we will show simple code examples and explanation to highlight how the feature enables rapid development of scalable, AI-powered applications.

Programming Abstractions for AI - by llm#

Jac provides novel constructs for integrating LLMs into code. A function body can simply be replaced with a call to an LLM, removing the need for prompt engineering. by llm() delegates execution to an LLM without any extra library code. For more information on by llm, check out more documentation here.

import from byllm.lib { Model }

glob llm = Model(model_name="gpt-4o");

enum Personality {

INTROVERT,

EXTROVERT,

AMBIVERT

}

# by keyword enables the program to integrate an LLM for the needed functionality

# Jaseci runtime automatically generates an optimized prompt for the LLM,

# checks errors and converts LLM output to the correct return type

def get_personality(name: str) -> Personality by llm();

with entry {

name = "Albert Einstein";

result = get_personality(name);

print(f"{result} detected for {name}");

}

How To Run

- Install the byLLM plugin by

pip install byllm - Get a free Gemini API key: Visit Google AI Studio

- Save your Gemini API as an environment variable (

export GEMINI_API_KEY="xxxxxxxx").Note: > > You can use OpenAI, Anthropic or other API services as well as host your own LLM using Ollama or Huggingface.

- Copy this code into

example.jacfile and run withjac run example.jac

Output

Introvert personality detected for Albert Einstein

Object Spatial Programming: Going Beyond OOP#

TTraditional OOP with python classes that expresses object hierarchy and behavior is fully supported in Jac. Additionally, Jac introduces a new concept called Object-Spatial Programing (OSP). Using OSP construts, programmers can express object relationships as graphs

- node classes (

node), - edge classes (

edge),

Instances of these node and edge classes form a graph structure that expresses semantic relationships between objects.

Computation in OSP occurs by traversing these graphs using two key constructs:

- walker classes (

walker), which encapsulate object interactions and specify how computation moves through the graph, - abilities (

abilities), special methods that walkers automatically execute when they visit specific node types.

OSP can be used where needed and maps nicely to many categories of problems, espeically those that deal with connected data, such as social network, knowledge graph, file system, dependency graph, etc. In particular, it is sepcially suitable for describing workflow in Agentic systems ;-).

By modeling relationships directly as graph edges and expressing computation through walkers, OSP removes much of the boilerplate needed to manage graphs, traversals, search and state. This makes complex logic simpler, clearer, and more scalable.

In the Examples section, you'll see cases where OSP cuts code size dramatically. For instance, we built an X-like social network (littleX) in just a few hundred lines, something that would typically take thousands using traditional OOP patterns. When combined with by llm, you can build sophisticated agentic workflows with minimal code - see our Agentic AI examples for real-world applications.

In this simple example, we aim to just illustrate the basic concepts. Here we have Person nodes, while walkers (Greeter) traverse the graph of Person objects and process them. For more OSP concepts, check out Quick Start, or Syntax Quick Reference.

node Person {

has name: str;

}

# Greeter can traverse the graph.

# start and greet are two abilities of Greeter

walker Greeter {

has greeting_count: int = 0;

can start with `root entry {

print("Starting journey!");

visit [-->];

}

# ability greet will only execute when Greeter enters a Person type node

can greet with Person entry {

print(f"Hello, {here.name}!");

self.greeting_count += 1;

# specify how this walker can traverse the graph

# in this case, visit all outgoing edges from the current node

visit [-->];

}

}

with entry {

alice = Person(name="Alice");

bob = Person(name="Bob");

charlie = Person(name="Charlie");

# specify the object graph, where root connects to alice, then bob, then charlie

root ++> alice ++> bob ++> charlie;

greeter = Greeter();

# root is where the graph starts, and we will start the walker here

root spawn greeter;

print(f"Total greetings: {greeter.greeting_count}");

}

How To Run

Copy this code into example.jac file and run with jac run example.jac

Output

Starting journey!

Hello, Alice!

Hello, Bob!

Hello, Charlie!

Total greetings: 3

To read more on how Jac/Jaseci enables rapid development of Agentic AI using combination of by llm and OSP, check out Building Agentic AI Applications with byLLM and Object Spatial Programming

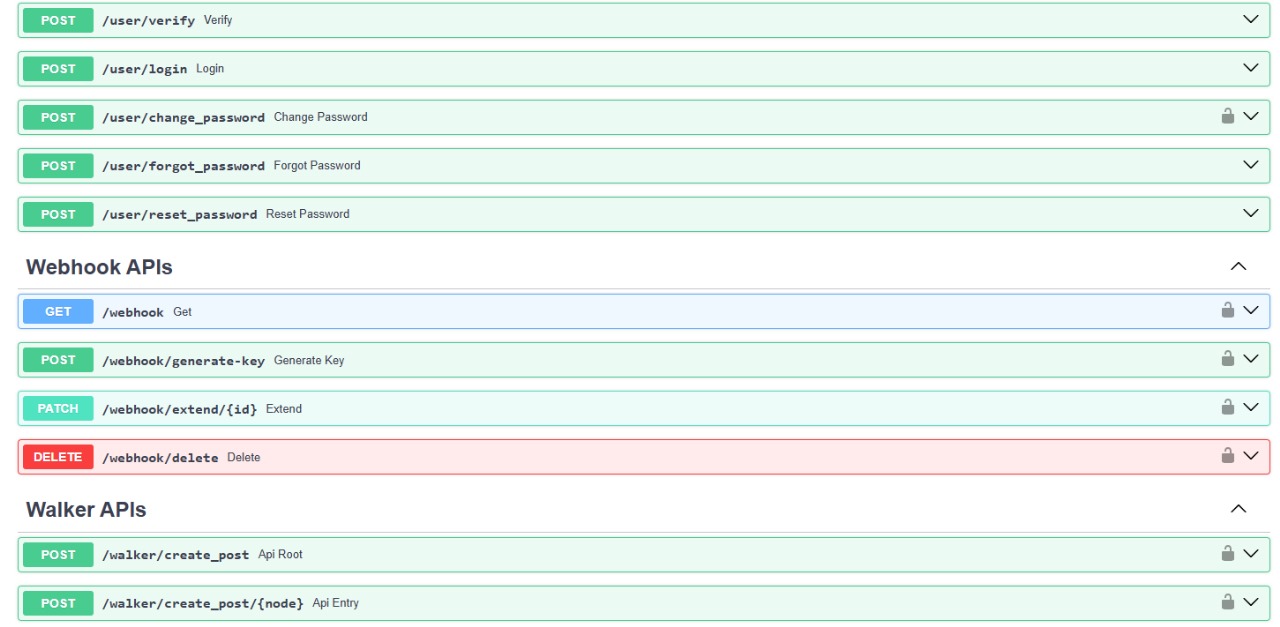

Zero to Infinite Scale without any Code Changes#

Jac's cloud-native abstractions make persistence and user concepts part of the language so that simple programs can run unchanged locally or in the cloud. Much like every object instance has a self referencial this or self reference. Every instance of a Jac program invocation has a root node reference that is unique to every user and for which any other node or edge objects connected to root will persist across code invocations. That's it. Using root to access persistent user state and data, Jac deployments can be scaled from local environments infinitely into to the cloud with no code changes.

node Post {

has content: str;

has author: str;

}

walker create_post {

has content: str, author: str;

can func_name with `root entry {

new_post = Post(content=self.content, author=self.author);

here ++> new_post;

report {"id": new_post.id, "status": "posted"};

}

}

How To Run

- Install the Jac Cloud by

pip install jac-cloud - Copy this code into

example.jacfile and run withjac start example.jac

Output

INFO: Started server process [26286]

INFO: Waiting for application startup.

INFO - DATABASE_HOST is not available! Using LocalDB...

INFO - Scheduler started

INFO: Application startup complete.

INFO: Uvicorn running on http://0.0.0.0:8000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

Python Superset Philosophy: All of Python Plus More#

Jac is a drop-in replacement for Python and supersets Python, much like Typescript supersets Javascript or C++ supersets C. It extends Python's semantics while maintaining full interoperability with the Python ecosystem, introducing cutting-edge abstractions designed to minimize complexity and embrace AI-forward development. Learn how we achieve full compatiblity and 5 ways you can use jac together with Python, check out [here] (https://docs.jaseci.org/learn/superset_python/).

import math;

import from random { uniform }

def calc_distance(x1: float, y1: float, x2: float, y2: float) -> float {

return math.sqrt((x2 - x1) **2 + (y2 - y1)** 2);

}

with entry { # Generate random points

(x1, y1) = (uniform(0, 10), uniform(0, 10));

(x2, y2) = (uniform(0, 10), uniform(0, 10));

distance = calc_distance(x1, y1, x2, y2);

area = math.pi * (distance / 2) ** 2;

print("Distance:", round(distance, 2), ", Circle area:", round(area, 2));

}

This snippet natively imports Python packages math and random and runs identically to its Python counterpart. Jac targets Python bytecode, so all Python libraries work with Jac.

Better Organized and Well Typed Codebases#

Jac focuses on type safety and readability. Type hints are required and the built-in typing system eliminates boilerplate imports. Code structure can be split across multiple files, allowing definitions and implementations to be organized separately while still being checked by Jac's native type system.

impl Tweet.like() -> None {

self.likes += 1;

}

impl Tweet.unlike() -> None {

if self.likes > 0 {

self.likes -= 1;

}

}

impl Tweet.get_preview(max_length: int) -> str {

return self.content[:max_length] + "..." if len(self.content) > max_length else self.content;

}

impl Tweet.get_like_count() -> int {

return self.likes;

}

This shows how declarations and implementations can live in separate files for maintainable, typed codebases.